Courtney Reimlinger was breastfeeding her week-old son last year when she felt a pain in her chest.

The pain was excruciating, the 23-year-old Indianapolis native remembers, much worse than the 10 hours in labor she'd spent a week before. It spread up her neck and into her head, and soon she was slipping in and out of consciousness.

"It was kind of weird how fast it was happening, and I was like, 'This isn't right'," Reimlinger said. "I had no idea it would be related to the pregnancy."

By the time Reimlinger made it to Community Hospital North, her blood pressure was 186/126 – a hypertensive crisis. She was diagnosed with postpartum eclampsia, a rare pregnancy complication that can cause seizures, strokes and organ damage.

Reimlinger spent a week in the hospital, away from baby Kallum, while doctors worked to lower her blood pressure.

"It was just a relief I got to the doctor when I did," Reimlinger said.

Read more: Troubled pregnancy can lead to years of health problems

Not all women in Indiana are as lucky. The Hoosier state has one of the nation's worst rates of maternal mortality – when a woman dies during pregnancy or within 42 days after giving birth or ending a pregnancy.

That's according to the United Health Foundation's America's Health Rankings Report, which uses data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In the United States, nearly 21 women die for every 100,000 births. Indiana's rate is more than twice that – 41.4.

That rate has been steadily increasing, according to data from the state Department of Health. In 2016, the most recent year data is available, 50 women in Indiana died from pregnancy and birth complications.

The numbers are so concerning that the governor signed into law this year a bill creating a statewide maternal mortality review committee. The legislation also requires health care providers to report when a patient under their care dies from pregnancy or birth complications. For the next five years, the committee will investigate each death and provide an annual report to the state Department of Health with their findings.

"We've got to get this fixed. We've got to make it right for moms who live in Indiana," said state Sen. Jean Leising, a Republican from Oldenburg and one of the bill's authors. "This committee, I believe, will really be able to delve into why."

Video: Experts maternal mortality and infant health

And there are a lot of questions: Why is Indiana's maternal mortality rate on par with countries like Mongolia, Cuba and Egypt? Why is Indiana's rate twice as high as its neighboring states of Kentucky, Ohio, Illinois and Michigan? And why, if maternal mortality has been rising for years, did it take so long for the state to do anything about it?

Maternal mortality and public health funding

The U.S. has the highest rate of maternal mortality of all developed nations. That's what Dr. David Boulware of Minneapolis started to read in headlines last year. The doctor of infectious diseases lives and works in Minnesota, but after reading several of these news stories, he became interested in how the nation stacked up compared to Indiana, where he went to medical school.

"The data exists, but no one had really put it together to look at trends over time," Boulware said.

What he found was "shocking." As the number of women receiving prenatal care decreased, the rate of those same women dying had "dramatically jumped" since 2008. In 2008, the state changed the way it collected data on deaths related to pregnancy and childbirth, which means data shouldn't be compared before then.

Boulware couldn't directly attribute the rise in deaths to any one factor. But he did notice patterns.

Funds for public health programs were decreasing. In 2017, Indiana received the least amount of federal funding for public health in the nation at $15.31 per capita, according to a 2018 report from the Trust for America's Health.

The federal funds come to the states as grants. Some are awarded based on need, and some the states compete for.

The state's investment in its own public health was even worse -- $12.4 per capita in 2014, according to the most recent data. The average state spent $35.77 per capita, the report found.

Public health funding pays for everything from tracking how disease spreads to creating community programs to educate and provide resources to those most at-risk.

"We find many of the poor counties that are the highest need are receiving the smallest amount of public health services," said M. Aaron Sayegh, a professor at Indiana University and health scientist who studies infant and maternal health.

Fewer opportunities to access care

Boulware also found clinics that provided affordable health care in Indiana, specifically Planned Parenthood offices, were closing. The state had 28 Planned Parenthood clinics that received federal family planning funding in 2011, Boulware wrote in a paper he published last year. By 2015, there were 18.

In 31 of Indiana's 92 counties, pregnant women must travel outside their county to give birth or receive prenatal care.

In 2016, 69.3 percent of Indiana mothers received prenatal care beginning in the first trimester, according to state Department of Health data. That could be in part because in 31 of Indiana's 92 counties, pregnant women must travel outside their county to give birth or receive prenatal care, Sen. Leising said.

"I have, for sure, two counties you cannot deliver a baby," said Leising, who represents counties or portions of southwest Indiana counties.

That means a doctor might not catch and prepare for pregnancy complications from warning signs like high blood pressure, diabetes or substance abuse.

Getting prenatal care is even harder for black women, the data show. While 71.8 percent of white women get prenatal care beginning in the first trimester, 58 percent of black women receive prenatal care.

There are also economic barriers to care. Women in poverty on Medicaid have access to good doctors and regular check-ups, Sayegh said. So do wealthy women. But the working poor, who might not qualify for government benefits and live paycheck to paycheck, can fall through the cracks.

The state has also lost some programs aimed at closing that gap. Nonprofit Bloomington Area Birth Services offered programs on breastfeeding and childbirth education. Most of its programs were free or on a sliding payment scale depending on income. It closed in 2015 due to lack of funding.

Georg'Ann Cattelona was the executive director of Bloomington Area Birth Services. After BABS closed, Cattelona continued to work with pregnant women and new moms, and she’s now on Bloomington’s Commission on the Status of Children and Youth.

"People could come in the first week postpartum and they could say, 'I'm still bleeding in a way I'm not sure is OK; I don’t feel good,' and they could help them figure it out," Cattelona said. "If you're at home by yourself, you'll probably be like, 'Oh, it's OK’."

Some of those programs have been resurrected around the state to address the high rate of infant mortality, or when a baby dies before its first birthday. The state Department of Health made reducing the infant mortality rate its top priority in 2013. Prioritizing infant mortality hasn’t helped the state maternal death rate, though. Infant mortality has dropped from 7.7 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2011 to 7.5 in 2016.

Creating a review committee

From a public health standpoint, the maternal mortality review committee is a good start, Sayegh said. But the way for the state to keep its pregnant women and mothers healthy is to create community-based solutions.

Every area is different, and what a mom like Reimlinger might need in Indianapolis could be different from what one of Sen. Leising's constituents needs in Rush County.

"Not trying to go and impose these programs onto the community, but understand what is best for the community," Sayegh said.

The 17-member committee is still being formed by the state health commissioner. Its first report isn’t due until July 1, 2019. Sen. Leising has been told there is interest in joining from across the state.

"Maybe in Indiana we just start doing something right," she said.

After a week in the hospital, Reimlinger was discharged with no permanent health issues.

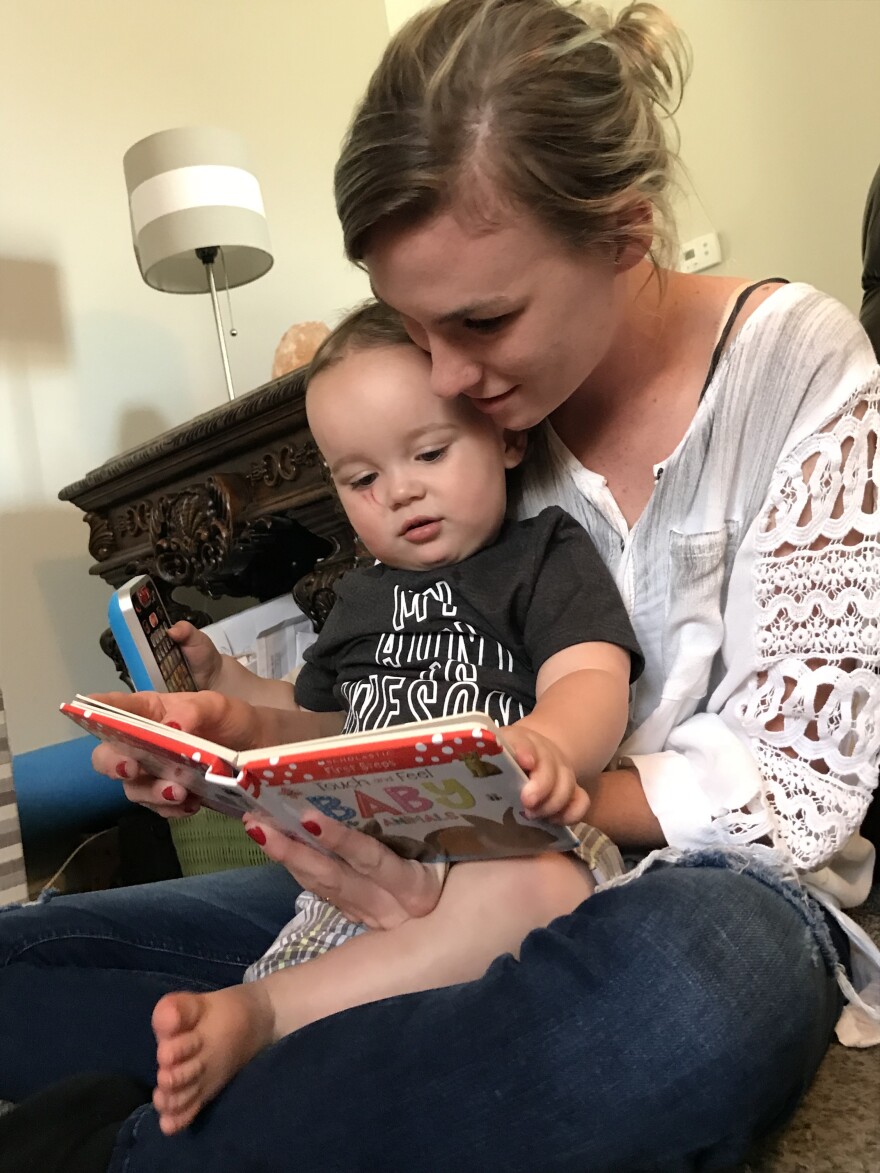

Now, 16-month-old Kallum toddles around unsteadily, exclaiming "uh oh!" when he falls on his bottom. Should his mom ever want to give him a sibling, Reimlinger knows that any future pregnancy will be high-risk.

"It's going to be scary, having another," she said.